Seattle in Black and White

Top of page photo credits: Seattle Municipal Archives photo, 63932.

Seattle CORE's Efforts to Create Equal Opportunity Employment in Seattle

Photo credits: CORE, Matson Collection.

Photo credits: CORE, Matson Collection.

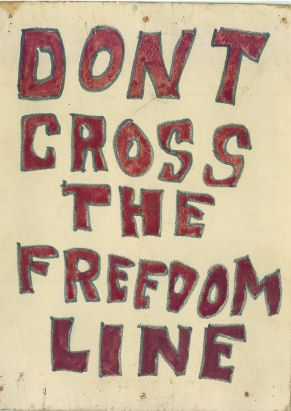

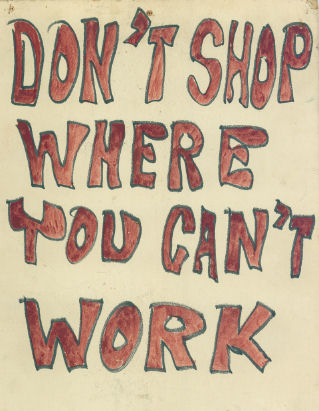

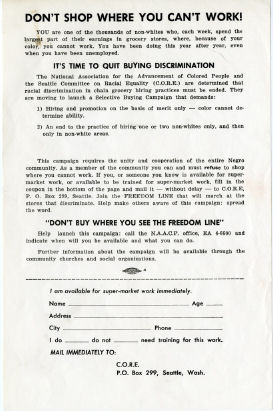

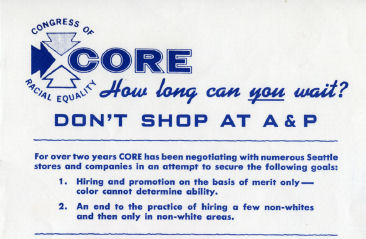

Jobs as clerks, cashiers, box boys, butchers, produce managers. Jobs that paid a living wage, jobs that put workers in front of the public were not available to Negro men in the 1960s in Seattle. Hard as it is to conceive how supermarket chains such as A&P, Safeway, Treadwell and others actually fought for years to keep Negro workers out. This all white reality was an every day, in your face, fact that could be seen daily by any Negro person who shopped for food.

Because of the customer-based leverage and because of the need for employment in Seattle's Negro community these chains became the focus for Seattle CORE's first employment campaign. Details of these activities including boycotts, picket lines and even a shop-in are available elsewhere (Singler et al, Seattle in Black and White, pp. 36-83).

Photo credits: CORE, Singler, Personal Collection.

Photo credits: Photo credits: CORE, Matson Collection.

The Congress of Racial Equality and the Fight For Equal Opportunity

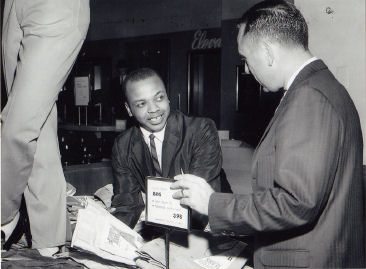

Although supermarkets were Seattle CORE's first target, there was no lack of companies and services that fit the same patterns. Seattle was a very segregated community. Department stores, including the Bon Marche, Nordstrom's, Fredrick & Nelson, I. Magnin and others did not hire Negro workers except as janitors, maids, and dishwashers. Fredrick's was particularly intransigent about its elevator operators and the Bon pointed to its "colored" waitresses in its plantation-themed restaurant. Others pointed to the matrons in the public restrooms.

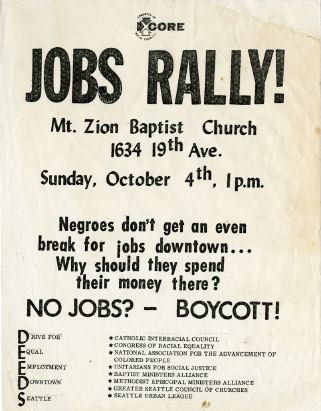

To dramatize the start of picketing, CORE would hold a large march to downtown. A date was set, Saturday June 15, 1963. Four days before the date set for the march the Bon capitulated and agreed to immediately hire Negro workers at its Northgate and downtown stores. But the march couldn't be postponed. The Freedom March stayed on schedule, but its focus was broadened to a general protest against job and housing discrimination in Seattle. The Freedom March was Seattle's largest civil rights event. It drew the attention of the media and put CORE on the Seattle map. The throng, 1200 strong and one third white, marched from Mt. Zion Baptist Church down Madison Ave. and ended in a massive downtown rally. This was a breathtaking first in Seattle.

The Bon Marche (later Macy's) became CORE's target. The Bon was particularly hostile. CORE asked people to turn in and not use their charge cards. This message went out broadly especially through churches and progressive organizations--a new CORE tactic. CORE was ready to use a boycott and picketing which was working well with supermarkets. But the Bon was a block long and a block wide and in the downtown core. Such a picket would require more organization, more trained pickets committed to non-violence, more trained captains and monitors.

Now was the time to meet with other downtown stores. Nordstrom was recalcitrant but a threatened "shoe-in" seemed to have changed Mr. Nordstrom's mind. Meetings continued with the Bon, Fredrick's, J.C. Penny whose store was at 2nd and Pine, Rhodes and MacDougalls. Fifteen to twenty negotiations were on going. Yet progress was slow. The November 1964 Corelator (the monthly CORE newsletter) noted "If Negroes in America continue to gain jobs in the future at the same rate...it will take over 700 years for Negroes to secure" numbers proportionate to their percentage in the U.S. population.

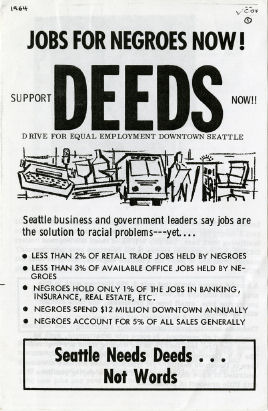

CORE decided to undertake a new Employment project on a much larger scale--all on downtown. It was named "Drive for Equal Employment in Downtown Seattle" or DEEDS. Details about the investigations, negotiations and activities of DEEDS are available elsewhere (Singler et al, Seattle in Black and White, pp. 77-82). In January of 1965 the CORE membership voted to suspend the downtown boycott. From our perspective decades later, CORE seems both naive and audacious in undertaking such a giant goal. That we tried is a testimony to our enthusiasm, our commitment, and our frustration at the slow pace to achieving equal racial opportunity in employment.

Photo credits: Barney Hilliard, reproduced by permission of DeGolyer Library, J.C. Penney Company records, 1902-2004, collection A204.0007, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas.

Photo credits: Photo credits: CORE, Matson Collection.

Photo credits: Photo credits: CORE, Matson Collection.

Photo credits: Photo credits: CORE, Matson Collection.